|

|

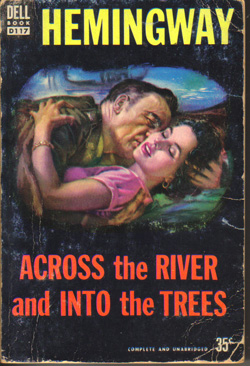

Hemingway: A Look Back |

His books are seldom read today, and his legend almost a faded memory. But in the 1930s and 1940s Ernest Hemingway was a literary idol--and role model for young writers who imitated his sparse prose and adventurous lifestyle.

Fame came to Hemingway early; while in his twenties, he wrote The Sun Also

Rises, a novel about American expatriates in Paris after the First World War.

Decades later, in 1957, a precocious graduate student named Susan Sontag

found The Sun Also Rises put her to sleep after only 54 pages; she briefly noted

in her journal the book was "dull," but finally finished it and several Hemingway

short stories. "What rot, as Lady A would say," she later wrote. (Susan Sontag,

Reborn: Journals & Notebooks 1947-1963, Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2008)

But to a generation whose values had been loosened by war and its idealism

shattered by a conflict that brought no lasting peace, the jaded expatriates

and bored aristocrats in The Sun Also Rises had great appeal; they were

unconcerned with money or materialism and instead were content to while

away their days in cafes or running with the bulls at Pamplona. This was--

in Gertrude Stein's words--the "Lost Generation," and Hemingway became

their bard.

Only years later would the image of Hemingway in Paris, the struggling young artiste, be exposed as a masterful public relations job. Married to a Southern heiress who supported him in high bohemian style, Hemingway dressed in bulky sweaters to appear muscular as he paraded around the Latin Quarter. His writing style derived from Gertrude Stein and Sherwood Anderson-- both of whom he derided in private. It was even hinted that the main character in The Sun Also Rises, the irrepressible Lady Brett, was borrowed from another novel. But, by the time these stories were published, years after the fact, the Hemingway myth was solid as Dr. Eiffel's Tower. (Morley Callaghan, That Summer in Paris, New York: Penguin Books ed., 1979)

Until his death--a suicide--in 1961, Hemingway was seldom out of public view. His technique was to embark on an adventure, then recapture it in a book. The Green Hills of Africa was based on a big game hunt the writer undertook; For Whom the Bell Tolls fictionalized the Spanish Civil War which Hemingway had covered as a correspondent in the 1930s.

The Spanish war novel was a Big Book with an important theme and so was a success with the easily guyed public and book reviewers. Hemingway had gained no insight into the Spanish character watching the war from Chicote's bar in Madrid where correspondents swapped drinks and stories. The novel's characters were hollow, made-up: gypsies, shepherds, peasants in black skirts. Moreover, the author's flat Midwest prose could not capture the rugged beauty of the Spanish countryside, and he did not understand the forces that roiled the Loyalist cause and would echo through Europe. Unlike Orwell, Hemingway failed to comprehend that the struggle pitted not only Left against Right but also the Left against itself.

Battles, boxing, bull fights: Ernest Hemingway was there, at ringside, celebrating the cult of manhood and danger. When the Allies swept into Paris and liberated the city, Hemingway, who was covering the war for Collier's, rode in with the troops. The author carried a pistol and was surrounded by an entourage that included a cook, a photographer, and a public relations officer that the Army had provided.

By the end of the war, Hemingway was world famous, his bearded face and massive body recognized everywhere. According to a biographer, movie stars and waiters alike knew the author as "Papa." (A.E. Hotchner, Papa Hemingway, New York: Random House, 1966) He stayed at the Ritz and maintained homes in several countries, including a finca in Cuba where he wrote, bred his fighting cocks, and held court to a stream of visitors from around the world.

But fame took its toll. Hemingway wrote for money and drank heavily. His lean prose became turgid. The long narrative had never been Ernest Hemingway's forte. Once, he said his novels had always started as short stories. A novel, To Have and Have Not, published in 1937, simply meandered, lacking structure or plot.

In interviews, Hemingway sometimes sounded punch drunk--using boxing or other sports analogies. On one occasion, he said: "Mr. Rimbaud...never threw a fast ball in his life..." referring to the 19th century French poet; on another occasion, Ernest told Marlene Dietrich, "You're the best that ever came into the ring." The novelist was widely quoted as saying, "My writing is nothing. My boxing is everything."

Hemingway's public persona became almost a self-parody. After surviving a plane crash in the African jungle, the author told the world press: "My luck, she is running good." Another time, he spoke of giving animals that he hunted, "the gift of death." A generation of novelists, major and minor--Mailer, Jones, Shaw--worshipped Hemingway's pseudo-toughness. But not everyone was bedazzled. One old friend, Canadian writer Morley Callaghan, was put off by Hemingway's "dumb Indian" pose. (This was before the dawn of Political Correctness.)

In The Old Man and the Sea, Hemingway wrote: "Imagine if each day a man must try to kill the moon. The moon runs away." Only the great Hemingway could have gotten away with such a ridiculous analogy; in fact, the slender book brought him his Nobel.

The Great Prize was widely considered the zenith of Hemingway's career, but at least one critic, Stanley Edgar Hyman, recognized the decline in talent the novel represented. Writing in The New Leader, an influential but small circulation magazine, Hyman noted: "From the sad truthfulness of The Sun Also Rises to the slush of The Old Man and the Sea, the progress of Hemingway's novels is a progress in increasing dishonesty, fake glamor, and success."

The author's pretentiousness became surreal. One evening dining at the Colony, a watering hole for the rich, Hemingway pronounced his table "a good querenica"--the area of the bullring where the bull repairs to fight. This observation was worshipfully noted by George Plimpton, a dining companion and editor of the Paris Review, a journal which had done much to inflate Hemingway's literary stock. (The Best of George Plimpton, The Atlantic Monthly Press, 1990)

Death, however, was not kind to her Prince. After Hemingway's suicide, stories surfaced that he had struck his wives and had beaten poet Wallace Stevens, an out of shape lawyer, over some minor literary quarrel. The Hemingway estate tried to suppress a memoir that revealed grisly details of the writer's shotgun death. The trial judge was unsympathetic, berating the late writer as a "despoiler of wildlife."

Ultimately, Hemingway's reputation would be hijacked by the academics and his novels turned into factories for new Ph.D.s. A rough and tumble writer, the late Charles Bukowski, dismissed Hemingway as "bullshitting." In 1987, Bukowski wrote of Hemingway and other "famous" writers of that earlier era: "I felt they were soft and fake, and worse that they... had never felt the flame." (Charles Bukowski, Selected Letters, 1987-1994, Virgin Books, London, 2005)

Now, it may be time for a reappraisal. For there is much to celebrate in Ernest Hemingway, especially those short stories he wrote before he became famous when he was a young writer in Paris. First published in obscure magazines and then collected in a book entitled, In Our Time, the stories are about knockabouts, Indian camps, fathers and sons, and innocent love: tales by a young man, about the young, yearning to explore the world out there--and live a life of wonderment and adventure.

Ron Martinetti for AL. This article has generated more e-mail than any other American Legends feature, mostly unfavorable. Tom Bertsch: "His books are seldom read today? His legend a faded memory? Thi s is how you lead on Hemingway? Who the f--k are you?" Tom Pierett, a Texas social studies teacher: "No, friend, you don't forget guys like Hemingway. After folks quit reading Stephen King, Danielle Steele and John Grisham, they will still be reading Hemingway. Count on it." Shawn Underhill: "Hemingway was not a perfect man, true, but he still deserves more respect than this. Whether or not it's fashionable to admit today, many writers owe a great debt to his style, consciously or not." Jo Jordan, British Columbia: "Personally, I was happy and relieved to read "His books are seldom read today...." Thank God was my thought. People have finally wised up to the fact that his writing is complete and utter drivel. With so many wonderful, talented contemporary writers, who needs to bother with that washed up wind bag?" Charlie: "Dear Ron, The style was simple at times and it is perhaps this simplicity which is most deceiving as to what is being said or at least implied. I have always thought that it is what Hemingway does not say that is most important to his works."

Macho Man

Fred Hasson, a contributor to Suite 101 on Ernest Hemingway: "Who is the fool that wrote the Hemingway article? I believe Ernest Hemingway is considered among the best short story writers--ever--the best in my opinion. His prose style influenced just about every writer who has put pen to paper since. Please change that page. It just makes your site look bad." Topsoul181@yahoo.com: "Whoever wrote the article knows nothing about writing. Not only is it utter rubbish, none of it is true. It's manipulative and ill-informed. I currently live in China, and can tell you that almost all high school students read Hemingway, and he is typically one of the only American authors they read." Alexander Ovsov: "It was a real pleasure to translate this into Romanian for my blog." Perry Anderson, college English instructor: "Papa had certain virtues, especially his ability to, in a minimal way, capture the essence of a place, and to convey, again minimally, the essence of conversation with all its ambiguities. However,he was also full of anti-Semitism and anti-feminism, and had a tendency to rush to judgment of those with whom he could not develop a sense of sympatico." L. Blair Torrey, Jr., former chair, English Dept., The Hotchkiss School: "I did teach several of his works, The Old Man and the Sea, The Sun Also Rises...and enjoyed working with them. I guess he's cyclical, like so many macho figures; he will last or will come back every so often. His spare style influenced my writing, somewhat like E.B. White's style in getting rid of superfluous words. He has some memorable figures: I'm thinking of Pilar and her husband ("Do not provoke me!") "There are few people who understand that in order to create we must first destroy. This author clearly understands this fact, for although Hemingway is great, he is not perfect." Robert Martirosyan, creative writing student." Ron can be reached at amlegends@aol.com

|

American Legends Features! |

|