![]()

| Seymour Krim: Bohemian Rhapsody |

In one of his poems, the late Lawrence Ferlinghetti noted that when they print your picture in Life magazine, you’re already a negative. This observation aptly applies to so many figures of the 1940s and 1950s who, after the light of fame shined on them, turned cool and commercial. Norman Mailer and Miles Davis come to mind, while others who remained in the shadows, seem somehow more interesting.

Among those who never received their due are Robert Phelps (1922-1989 ), the co-founder of Grove Press, whose graceful essays on James Agee and Colette remain fresh as ever, and Seymour Krim (1922-1989), the avatar of hip whose failure to achieve fame was not for want of trying.

In a way, Seymour seemed destined for his role. Orphaned at 10, Krim grew up on the West Side of Manhattan, bounced “from home to home” by relatives. Self-pitying and “wildly insecure,” young Si hated being “a big city Jewish boy,” bookish and shy, and wished he could be a tough, blue-eyed Irish kid. Always “rebellious,” he refused barrmitzvah, and at 17 “had my beak clipped” to appear more gentile.

It was only later when he fell under the influence of a self-taught intellectual named Milt Klonsky that Krim dug his heritage and developed a cool admiration for the intellectual intensity of the smart Greenwich Village “J” boys, as Seymour called them in his breezy style.

Early on, Krim yearned to be a novelist. American life was “my scene,” as he put it, and he “gobbled up novels by the shelf-full of Theodore Dreiser and Edith Wharton.” At DeWitt Clinton High School in the Bronx, Seymour got in hot water for publishing “a dirty-word lit magazine called Expression.” (What’s This Cat’s Story? The Best of Seymour Krim, Paragon House, 1991) The aspiring author also made a pilgrimage to the Village to interview James Agee whose poetic approach to journalism as a writer for Fortune was beginning to attract attention.

For college, Seymour headed to the University of North Carolina–Chapel Hill–whose halcyon campus Thomas Wolfe, another early literary hero, had celebrated in his great novels of the thirties. But Krim flunked out and soon found himself back in New York City.

The Greatest Generation was off to save the world, but storming beaches had no allure for young Seymour, and he wound up “ducking the war” in the Office of War Information, writing news stories for eighty-five dollars a week. He spent his nights roaming Harlem looking for ladies and weed, adventurers he would later chronicle in an essay, “Ask for a White Cadillac,” after he had developed his naked, introspective style.

In the spring of 1945, Seymour met a Village neighbor, Milt Klonsky, and his world changed. He went from wanting to be “F. Scott Krim” to Si Krim, a “smart ass”–the description is his–critic who put down literary lions at cocktail parties and generally made himself obnoxious to whomever was around.

Klonsky had gone to Brooklyn College, read everything, and was at home in abstract thought. He had “no sense of Jewish inferiority,” Krim noted admiringly of his new friend. Klonksy’s self-confidence was boundless. He “was grooving,” Seymour would recall, “a jazzy kid with a chick under each arm, there was nothing in the slightest Lionel Trillingish about him.” The latter was Si’s dig at the prim Columbia University professor, a Jew, whose speciality was the English poet, Matthew Arnold.

Sometimes high on pot, the lights low, in the blacked-out war city, Seymour, Milt, and Milt’s wife, Rhoda Jaffe, would lie around the Klonskys’ one room apartment, and listen to Milt’s “far out imaginings.” Rhoda was blond, beautiful, Jewish. Milt had met her at Brooklyn College where they formed an intellectual circle that included Chester Kallman who was W.H. Auden’s lover and sometime librettist. Such was Rhoda’s beauty that she later seduced Auden whose interest in women was usually platonic.

After undergoing electric shock treatments following a nervous breakdown, Krim could “remember few of [Milt’s] exact quotes”–and was left only with recollection of Klonsky’s “brilliant poetic instrument-panel of a mind which created before one’s eyes idea-designs and thought–organizations that had no precedent.”

Klonsky went on writing criticism for Commentary “to make bread” and storing up for a great poem–“a Cathedral work”–that went unwritten. (Seymour Krim, Views of a Nearsighted Cannoneer, E.P. Dutton & Co., Inc., 1968 ed.)

Despite Klonsky’s influence, Krim’s writing following the war remained conventional, thoughtful reviews in highbrow journals on Ernest Hemingway, Thomas Wolfe, and Edmund Wilson, an influential critic for The New Yorker who was a pillar of the square literary Establishment.

Later, in “What’s This Cat’s Story?”- a 1960s essay- Krim described his early reviewing as “a thruway to nowhere.” Writing for Commentary and The Partisan Review-he felt- gave the “avant young writer” the “ most superior feeling of having made it” when actually he was “copying his elders’ manners...and being dishonest to himself and his own generation in the way he expressed himself.”

Outwardly, Krim’s literary career moved along, though he still hoped to someday write fiction. “Like every creative type of my generation whom I met in my 20s,” he would explain, “I was positive I was sanctioned, protected by my genius, my flair, my overriding ambition.”

Inwardly, Krim remained insecure, sexually and otherwise. There was an unsatisfactory homosexual –to use a word then in vogue–affair. He would destroy his private journal and “burn letters I had received through the years from several men and women I had loved.”

Seymour was 33 when it all came undone. It was 1955, and one day he flipped, running through the streets barefoot, exposing himself to strangers. Somehow, he wound up at the posh St. Regis Hotel off Fifth Avenue where he was cornered by the cops and carted off to Bellevue–the city nut ward.

Transferred to a private sanitarium in Westchester, Krim underwent various therapies but still believed that God had given him “the right and duty to do everything openly” and act out his fantasies. He was smart enough, however, to stand up in therapy class and "humble" himself to earn his discharge.

Too “ashamed” to go back to the Village, Krim holed up in a cheap Broadway hotel. Sitting in a bar one night, feeling suicidal, he saw a girl doing a Polish folk dance. Her “saucy, raucous” movements lifted his spirits, and he broke into “loving sobs like prayers” over his drink. “The sun of life blazed from her into my grateful heart,” he later wrote in “The Insanity Bit,” a long essay about his ordeal.

When Seymour shared his epiphany with a psychiatrist, he was bundled into an ambulance and wound up in “another hedge trimmed bin in Long Island.” In between shock treatments and watching “Gunsmoke” on TV, Krim concluded that the sanitarium was like Grossinger’s, the Catskills resort, where middle class Jews spent their summers. The bill was footed by Seymour's uncle, Arthur Krim, a wealthy lawyer and Democratic party stalwart. (Neither wanted the family connection to be known, for different reasons.)

The smooth house psychiatrist tried to get Seymour to admit his life was “a lie,” that his bohemian values lay at the root of his problems. The doctor even put down Greenwich Village as a “psychotic community.”

Si wasn’t buying into the program. He “could not and never would” repudiate his former life, Krim later wrote–a life of “experimentation, pursuit of truth..and non-commercialism,” in favor of “middle class propriety with the cut-throat reality of money underneath.”

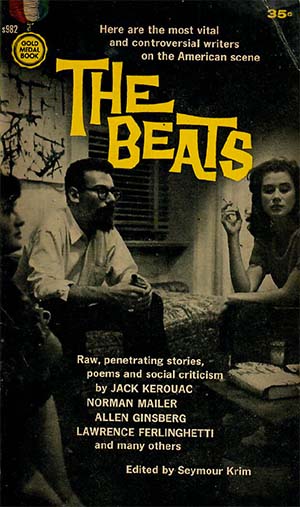

It took a close friend to do the “dirty in-fighting,” but Seymour won his release. Finally, he was back home “walking down 8th Street a gratefully free neurotic.” Again, his life was his own, and with it came a feeling of liberation. Later, he would wryly note: “Let his 64 ex-psychiatrists rejoice in the fact that he is no longer afraid to accept responsibility–for helping to blow up the square literary world.” (Introduction to The Beats, ed. by Seymour Krim, Gold Medal Books, 1961)

And, true to his word, Krim tossed out the “cramped way of writing life” of The New Yorker and in its place splashed across the page Klonskyesque dialogues between himself and the reader in which he piled image upon dazzling image, shaking it for all the world to see. “It represented a breakthrough for me,” he later recalled, “unlike anything I had experienced in my ball and chain literary days.”

From 1957 to 1960, Krim spun out his essay on Klonsky, in addition to “The Insanity Bit,” and his memoir of Harlem: a prose poem of gorgeous nights in the city within a city, caressed by jazz and the Magic Lady.

More than any other white writer, Krim understood not only the attitudes but–more importantly–the etiquette of hip: how to look sharp, every crease pressed, “riflehard and classy;” how not to stand with your back to the bar, facing the crowd. It made you look conspicuous and was “in bad taste.” And the cardinal rule: always “show courtesy and good humor when put down” by a lady high on heroin.

Several essays were published in Exodus, an underground magazine, and collected in Views of a Nearsighted Cannoneer;” the title was Si’s private joke at a career spent “hoping to turn America on its ear with words shot from a cannon.” A paperback original, the book was underwritten by an admirer and came out in 1961. When the patron ran short on cash, Seymour’s essay on Milt Klonsky was “chopped,” and “with it went a bit of my life.” (A decade later, the essay was reinstated in a revised edition.)

By the 1960s, Seymour had attracted a literary following in the Village and among practitioners of the New Journalism who were influenced by his essays that broke down the wall that traditionally separated the author from his subject. He was ignored by the king makers–The New York Times or the Luce empire–who bestowed their royal favors on more acceptable writers, like Norman Mailer whose books sold well, or the “young Rev. Updyke,” as Krim called him, whose view of the world was polite and well-ordered. Later, Si would recall that the Times “hadn’t even thrown me a one paragraph review” when Cannoneer was published.

The cracked mirror Seymour held up to society reflected his own perceptions. This attitude came through in his encounter with Dr. Joyce Brothers (1927-2013)–“the most formidable JAP (Jewish American Princess) in the country.”

Seymour tried to interview Joyce in the late sixties, gave up, then recalled the experience in a 1980 essay in which he concluded that at bottom his hostility to the popular psychologist stemmed from “juvenile, scarlet-envy.”

Krim knew that “straights and non-straights” could “never be totally at ease together,” but his discomfort with Joyce ran even deeper. He and the psychologist came from “opposite poles of New York Jewish need and intensity that practically led to civil war when we met.”

Joyce was poised and attractive, a prodigy who had zipped through graduate school at Columbia University and gone on to a successful career as a newspaper columnist and television personality; the first time Seymour saw her was on a quiz show where she won a bundle on boxing arcana while he sat on a folding chair in Bellevue watching television.

The psychologist might have been “a fraud”- a sly reference to the rigged quiz show, though Joyce insisted she was never slipped the answers–but Seymour could not “undress her in public.” She loved the spotlight,” just as “a certain small-time writer I knew,” he concluded, but his “straight JAP sister” had made it in the big leagues of mass communication by working “harder and more consciously than I ever had for all my anti-establishment thunder.”

Milt Klonsky had taken a job reading manuscripts for a vanity press; Seymour ventured even farther outside the bounds of intellectual respectability when he became editor of Nugget, one of the “girlie” magazines that splashed across newsstands in the early sixties. It was an arresting marriage, between highbrow and low. Seymour used the “sassy mass-publication” to showcase the work of young writers, like Dan Wakefield, or boost the reputation of others, like Jack Kerouac, whose novel, Desolation Angels, Seymour had written the introduction for, and whose reputation had been flattened by years of attacks from critics, like Norman Podhoretz who had dismissed the Beats in an essay entitled “The Know- Nothing Bohemians.”

Wakefield, who hung out with Krim at the White Horse Tavern , and later wrote a memoir, New York in the 1950s, remembers Krim’s loyalty: “ He commissioned me to cover the trial when The Provincetown Review was banned in Boston. It paid me 500 dollars, a King’s Random then. Looking back on our friendship, I think the word for Krim is: He was a mensch. Compare that to Jack Kerouac’s whining and hating on everyone.”

At one point, Seymour was hired as a manuscript reader by Otto Preminger, the Hollywood producer who had a New York office. Wakefield recalls an episode from that mismatch: “ I’ll tell you a story. One day Seymour called me and said: ‘If you hurry and get here by noon, I will be able to take you to lunch at a good restaurant on my expense account. By 5:00 P.M. I will be fired.’ I rushed uptown, and Krim took me to some place, I forget which, and we had Bloody Marys and a good lunch. He explained what had happened: ‘When I sent Otto the last batch of stories I recommended that he read, I slipped in a story I had written but didn’t put the authors’ names on any of the stories. After he read them, he called me in and handed me the story I had written which was anonymous. He said, ‘Why you give me this chicken shit?’ I confessed it was something I had written myself, and he said: ‘You’re fired. Be out of here by five o’clock.’ We toasted our Bloody Marys and had a great lunch. As I said, Krim was a real mensch. The first thing he did hearing he was fired was to call a friend and take him to lunch while he could.”

The Nugget gig lasted four years, a lifetime for someone as peripatetic as Si Krim; then there was a stopover at Show, a glossy magazine started by an eccentric art collector, before Seymour signed on as a “common city side reporter” at the Herald Tribune, just before that paper folded. The idea was to join the verve of fiction writing with daily fact based reporting and create Art (as Gay Talese and Tom Wolfe believed they had done).

It was the Lindsay era in the Big Apple, full of strikes and drama, but Si’s snapshots of city life lacked the zip of Cannoneer. After all, no matter how liberal a Republican the paper’s owner, Jock Whitney, might be, Seymour could not put on Park Avenue breakfast tables how he had balled through Harlem (four to a room) the night before.

Seymour loved the Trib, the "scoop the town journalism," and boozing after hours with Jimmy Breslin and the boys. Jimmy's beat was the outer boroughs; his column was filled with tales of New York characters, like Marvin "the Torch," whose calling was assisting failing businesses to collect insurance payments.

When Seymour looked back on those days, however, it was through the lens of a critic, and in 1970 he wrote that Jimmy and other New Journalists, like Tom Wolfe, "didn't always tell the whole truth" in their "highly colored...versions of events." Breslin might have let this pass, but in discussing the sale of his nonfiction novel to the movies, Krim quoted a gleeful Breslin as saying that he had gotten "a quarter of a million bucks" out of two Hollywood "Jewboys."

Seymour hadn't been offended by Breslin's use of the term. In hip circles, that would have been uncool. Sometimes, he even referred to himself as "a boogie-woogie Jew." Then, Breslin sued, claiming Seymour made him appear "anti-Semitic."

The irony was not lost on Seymour, and for two years he was "knocked down by Breslin" and ostracized by their friends. Finally, Jimmy dropped the case--"without saying boo."

Seymour figured Breslin had only filed the claim not to lose the "patronage" of the "cynical" city power brokers at Toots Shor's, but the "nightmare" left Krim feeling like a "smalltime Judas" to the big Irishman's "pop, commercial Christ." (Essays from You & Me (1974) retrieved from the Stacks Reader, November 2, 2021)

Seymour resented the lack of recognition his work received, even among the “literary–sexual–intellectual-avant garde.” He “...always felt, and always will feel, every inch an equal to Mailer.” As Dan Wakefield puts it: “Krim created that nonfiction form that Mailer later copied. Mailer even mentioned it once, but Krim still gets no credit.” Wakefield never “felt self-pity” in his Krim or his work: “If he was tormented, it was because he was always broke, always trying to dig up the next buck. He never got the recognition he deserved.”

It was little consultation when an acquaintance assured Si that “When you go to a party anywhere in New York at least one person will know your name.” This compliment was passed at a sparse Christmas party and only brought down Krim further. Later, he dismissed the well-meaning speaker as a “fag” who dressed windows for a living.

At the root of Si’s feeling of failure was the knowledge that he “...never became the marvelous novelist of my teenage ambition.” He could not shake the romantic hold the novel had on him when as a boy he had locked himself away reading, and visions of young Studs Lonigan and Gloria Wandrous never stopped dancing in his head. The critic could not run from the reality that he never put on paper those stories that captured “my own mad love affair with the fabulous diversity of this society” and the “big gaudy continent” that was America.

Klonsky was steeped in Freud and Jung; he had instructed Seymour to be rigorous in his self-analysis. “Those of us who have never nailed it down,” Krim wrote in “For My Brothers and Sisters in the Failure Game,” undertake “the endless review of our lives to see where we went wrong.”

Seymour never flinched from the verdict he reached: “I was self-deceptive, self-indulgent,” he confessed, “crying inwardly for the pleasure of a college boy even while in my imagination I saw myself as another Ibsen or Dreiser.” He may have lacked the discipline to write novels, Krim admitted on more than one occasion; or “could have been an uncertain performer at whatever I did.”

Somehow, he just couldn’t free the genie who could tell that Wolfean tale of a Jewish orphan who longed to be a handsome Hollywood star–a Robert Taylor–but who instead tasted the “sweet cream” of uptown and Village life while the world was at war.

And like Milt Klonsky, or Tony Broyard, another member of their circle whose long awaited novel went unwritten, Si spent too much talent on journalism of one kind or another. Krim recognized this himself when he wrote that shortly before he died, James Agee had told a friend: “I wasted it all. I should have written only poetry.” Substitute novels for poetry–and you have Seymour’s epitaph.

Anyway, Krim knew that “one life was never quite enough for what I had in mind.” He lived alone, his possessions were few. There were too many mornings when he woke up to “an unmade bed and a few unwanted cups on the bare wooden table of a gray day.” He supported himself through free lance assignments and teaching stints at Columbia and Iowa: “a poor second to what I wanted.”

Krim once asked in an essay: “When do you stop fantasizing an endless you and try to make it with what you’ve got? The answer is never, really.”

For a time, Krim lived in London with a “soulful Italian girl out of Australia;” it was a relatively happy period away from “the Bitch of Manhattan,” during which he traveled the continent. There had been another happy interlude in the early sixties when Seymour struck up an improbable friendship with Joan Blondell, the blond actress who had appeared with Jimmy Cagney in Floodlight Parade, the 1930s movie in which she played his lovesick secretary. She and Si were a pair, though it seems not in bed. As he recalled in an uncharacteristically upbeat essay, they would dance cheek to cheek on her Sutton Place terrace, and she would “dish” him Hollywood “dirt” about her ex-husbands. Dick Powell was a “hick from Kansas,” she once told Seymour about the onetime matinee idol, which must have been music to Si’s sharp critic’s ear. After Joan returned to the West Coast, it was she who ironically wrote a novel, Center Door Fancy, about her Hollywood years.

In the late eighties, Seymour’s health began to fail. Faced with the prospect of being ill and alone, Krim took his own life in August 1989. Years before, in one of the magazines he edited, he had written of suicide: “In a living room debate what swinging adult has not conceded that existence can be more of a curse that a benefit and that an end to life can often be more ‘sane’ that a perpetuation of endless Tuesdays of suffering.” The critic’s death was reported in a one paragraph story in the back pages of The New York Times.

Seymour’s sudden death deeply affected his friends, like Dan Wakefield who recalls: “ In a letter I was sent after Seymour decided to end his life, he said: Don’t be sorry about this. I had just come to the point where I couldn’t physically live alone as I always had done, and I didn’t choose to live with ‘assisted care,’ or whatever it was called then. He then went on to praise my last work, encouraged me to go on, keep writing, do my stuff, and told me what a good friend I had been."

Ron Martinetti for AL. Ron would like to thank Dan Wakefield for his many e-mails (2012-2013) regarding Seymour and his circle. Dan is the author of Going All the Way, a popular coming of age novel that was made into a movie starring a young Ben Afflick and Rachel Weitz. Today, Wakefield lives in his native Indianapolis and writes on spiritual themes for his website.