The modern American novel, in its most serious form, is a study in sociology: There is Sister Carrie, Theodore Dreiser’s early novel of Chicago, the mighty city that sprang up from the mud of the prairie, and The Day of the Locust, Nathanael West’s portrait of down-and-out characters that ringed the glamorous Hollywood film colony.

Among these two classics, there are no doubt others, but alongside of them should be placed City of Night, the 1963 novel that tore back the blanket that had shrouded the American night and revealed a dazzling world of “scores” and “hustlers,” well-healed “Daddies,” and their kept male lovers who wore “a collar like the wicked queen in Snow White.”

It was Main Street and Pershing Square, L.A., and Times Square, New York. “This is clip street, hustle street–frenzied-night activity street,” wrote the book’s author, John Rechy, a young Texan, who had landed in L.A. after college and the army with a vague idea of becoming a writer. “This was the world I joined.”

Rechy was born in El Paso, the son of a devoutly religious mother and a father of mixed Scottish-Mexican ancestry. In Mexico, the father had been a gifted musician and band leader but had been forced to flee in the revolution that overthrew Porfirio Diaz and had landed in the hardscrabble border town where he eked out a living as a musical tutor to “untalented, grudging Texas children,” as his son remembered in his autobiography. (About My Life and the Kept Woman, Grove Press, 2008)

Money was scarce; and childhood was a series of dilapidated houses under the bitter roof of a father whose intimacies with his son were such that even the author’s avant-garde publisher toned down when his first novel was published.

Rechy’s mother was beautiful, in the way that Spanish women are, and adoring of her son, Johnny, whose fair features set him apart from other children in the barrio of South El Paso.

As with many a lonely lad, there was escape in the movies of Hollywood–Tyrone Power–and the oasis of the public library where the future author discovered Hawthorne, the romantic novels of Emily Bronte, and Poe whose style he copied in a story.

Sunday afternoons were an escape in which Rechy would wander the banks of the dried-up Rio Grande or climb Cristo Rey, the mountain that overlooked the city, in the company of a “wild-eyed girl” who shared “the same wordless unhappiness I felt within myself.”

High school proved a series of snubs at the hands of Anglo–white–El Paso; then, it was onto a local mining institute, which Rechy attended with the help of a scholarship from the El Paso Times where he worked part-time as a copyboy. The school had a small English Department; and there he was introduced to the English classics: Pope, Donne, and Milton, about whom Rechy wrote a paper, arguing that the great blind poet “was on the side of the rebellious angels.”

Already, at college, he introduced himself as “John, I’m a writer.” And, already, a part of him remained hidden from the world, avoiding telling others that he lived in the “projects,” as to not be identified as a “poor Mexican” by affluent students drawn to his intelligence.

All along, there was a drive to escape El Paso–the fierce heat, the prejudice everywhere, the small-town gossip. On one occasion, some jealous aunts told Rechy’s mother that he had been seen in the company of an “effeminate” older man–a former theater director stationed at the nearby army base who had taken an interest in the bookish young man.

Under the circumstances, Rechy welcomed the draft, even though the Korean War was underway. He found himself in the 101st Airborne Infantry Division, the fabled Screaming Eagles. He got to wear the Screaming Eagles patch, but, for him, the army was service details and an icy Kentucky winter. What Private Rechy took away from basic training was an aversion to killing.

When his orders came, they were for Germany; and, in Frankfurt, the future author guarded over the ruins of a past war. Escape was the base library where he read Henry James’s The Ambassadors, and poet James Thompson who used a phrase that remained in Rechy’s mind, City of Night.

Leave meant an excursion to Paris, a city still glowing with the joy of liberation. He visited the Louvre and the Café de Flore, the haunt of Sartre and de Beauvoir. Everywhere Rechy went, attractive women and men filled the boulevards. One night on the edge of the city, he found himself dancing with another young man. “It was as if I had suddenly awakened from a long, long dream,” he later wrote in his autobiography, “and into reality.” In Paris, the blurry shadows of his life were slowly coming into focus.

After his discharge, Rechy headed for New York, hoping to enroll in a writing program at Columbia University on the G.I. Bill. As his application, he had submitted a novel with a Mayan theme that he had written back in El Paso.

He arrived in New York by Greyhound bus and checked into the Sloane YMCA near Times Square. A rainstorm slashed down on the city. Shortly, he learned that he had been turned down by the head of the program, Pearl Buck, whose pseudo-Chinese novel, The Good Earth, had made her famous; in her rejection letter, she wished him luck in his career.

Almost broke, the would-be author hung around the Y, “lonesome, afraid.” A tough seaman told him, “A good looking guy like you” could pick up some cash in Times Square. “You just stand there.”

The city was a “dull gray” the afternoon Rechy wandered over to Forty-second Street. Young men were lounging about, under the blinking neon lights and pinball arcades. Rechy recognized “the dance of the streets...an extension of the world I had entered in Paris.” He had an urge to leave...buy a ticket back to El Paso. A man in a business suit approached and offered to buy him dinner.

And so, the author “stepped into” a new world, one of rented rooms, chopped from once elegant apartment houses, all-night movie theaters, and bars with “streaking mirrors” and “hungry eyes.”

Quickly, he learned the “rules for existing on the street.” It was a transactional world, devoid of affection.

“A rigid set of requirements was evolving for my life on the erotic streets,” Rechy later wrote in his autobiography, “and the main one was this: to be desired without reciprocation.”

Periodically, he would flee, using his army training as a court stenographer to work as a paralegal. He would then have funds to send to his mother since he would never send her “street money.”

Always, he would return to “the turf,” even when he was working; and “the uncommitting admiration it affirmed.” The wild city nights melted into cafeteria dawns that then emptied, just before families appeared for Sunday breakfast.

Rechy knew it was time to move on when “young drifters” appeared on the scene and stole the attention. It was fall in Manhattan when he left with his duffel bag and typewriter, leaving behind “the island city” with its strangers who passed each other on the streets “like mechanical dolls,” knowing “new people would replace me on Times Square and in the park….”

Ultimately, his destination was Los Angeles where a sister lived, and there he would make a permanent home in the city where the freeways swirled in semicircles and the bright sun sank into a black ocean.

In a matter of days, he found his turf in “the ratty world of downtown LA,” among the pawnshops and the action in Pershing Square where young hustlers waited, just a glance away from the statue of a disheveled Beethoven.

It was a strange scene he had hit upon: parks that crawled with the vice squad, some of whom shared their quarries’ proclivities, and a “spade bar” on upper Broadway. Always, life was lived in the night. In later years, whenever he heard the song, “For Your Love,” Rechy would think of L.A.

Everyone had a story. The future author listened but never took notes. He didn’t want to “betray that world” and “Allow the stories of the people I had lived among…to provide my own escape when there was none for them.”

In the mornings, Rechy read Proust in the “stone temple” downtown library, just a few blocks from Pershing Square where he soon got to know the regulars, Chuck, the original urban cowboy with his sideburns and jeans, who swore he was straight; and the “fabulous” Miss Destiny with her flaming red hair—“a giant firefly”—who dreamed of the life she would one day lead “in a beautiful home with a winding staircase.”

There was also the distinguished “professor,” an old queen, in his sickbed, taking the case histories of young men—like the Chicago sociologists did in The Jack-Roller—but fondling them between sessions. When Rechy recounted this adventure, he changed the location to New York to protect the scholar’s identity.

It was, he would later write in City of Night, “a compulsive journey through submerged lives”; and, like so many adventurers who one day would sit down and put pen to paper, it happened almost by accident.

He was drawn to New Orleans—Carnival—where for a week the natives paraded in gaudy costumes and visitors reveled in French Quarter bars and cheap motels, ending on Ash Wednesday, the advent of Lent, a time of Penance and mourning.

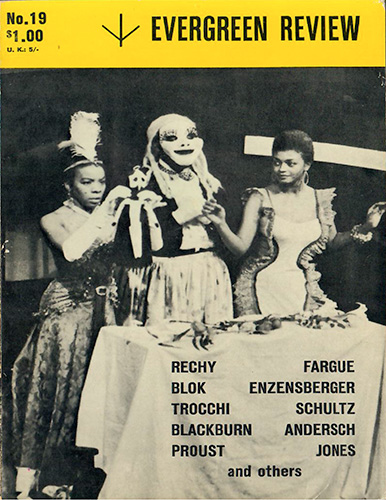

Back in El Paso, Rechy retreated to his mother’s apartment in the projects. There, he was overcome by the “infinite sadness” that had so often trapped him as a youth. Days passed in which he was paralyzed by depression. To escape, he rented a typewriter and wrote a letter about his New Orleans adventures to someone that he hardly knew, a friend of a friend. He tucked the letter away, then retrieved it a few days later; and, after a few revisions, sent it to the Evergreen Review.

The slush pile does not often draw such submissions—hence, its name; but a talented editor, Don Allen, knew he had found a gem. “Mardi Gras” was published, and its young author encouraged to write about others that he had met in his picaresque adventures, which he reluctantly did over the following four years.

Woven together, the stories became City of Night. The book was a New York Times best seller (probably to the chagrin of the Good Gray Lady). Some reviews praised the book’s originality, others were “strident,” as Rechy put it, including that in The New York Review of Books, whose critic, Alfred Chester, resented the sudden success of an outsider. It was thirty years before the journal allowed Rechy to submit a rebuttal.

A more balanced review was offered by the poet and critic Frank O’Hara. (1926–1966) Writing in Kulchur, O’Hara called City “one of the best first novels in recent years,” and described the author as “a master at getting the distinctive and odd quality of a city or a quarter or a milieu into his prose.” O’Hara also quoted a friend as saying of the book: “I like it, but why are gay novels always so sad?”

In the years since publication of City, Rechy has lived in Los Angeles, teaching a private writing seminar—and writing, including the acclaimed novel, Numbers, which Rechy has described as “a favorite among all my books.”

This interview with the author took place in his pleasant home high in the Hollywood Hills, overlooking the city “of lost angels,” that he wrote about in City of Night.

JR: Gide was quite an influence. I loved his elegant reflections on art in The Counterfeiters, and this influences what I do with my work. Also, I loved The Immoralist.

JR: Not at all. They came before me, though we did overlap. I never joined any identifiable group, but I did enjoy them.

JR: Everyone was influenced by "Howl". It was a bombshell. But can I really say he influenced me? No. I admired him. Later, we met. He invited me to visit him. He was amusing with his incense and his candles. We also did a reading together. He would not shut up.

JR: Who would I have liked to play the main character? Young Monty Clift. I liked him very much. I had seen Red River. He was a tremendous actor. So sad.

JR: I didn’t gravitate toward groups. I don’t know why. There’s a distrust. I don’t like gay literary groups. The ghettoization and incestuousness. It is as though only they exist.

JR: Yes. My good friend Gavin Lambert. He wrote one of the best books set in Los Angeles, The Slide Area. Also, James Purdy who wrote Malcolm. There’s a real writer. He was very mistreated. Still is.

JR: I would go downtown to the library to read. Thomas Wolfe’s Look Homeward, Angel moved me, and Faulkner’s Light in August. But writers often will not say who influenced them, like Kathleen Winsor whose Forever Amber I read, even though our church banned it.

JR: Yes, there were comic books, like Flash Gordon, which tried to pull the reader back, and movies like Body and Soul [with John Garfield]. When I was writing City, I listened to the music of Elvis Presley and Fats Domino, which I tried to capture the rhythm of.

JR: It was shocking. It pursues me, even today. He was a terribly disturbed man. Gore Vidal wrote a review to try to rectify it. Later, Vidal did a nasty interview in one of those journals I didn’t read–Partisan Review–saying that at some point he could have gone on to write John Rechy novels but chose not to. It was so bitchy. Years later, Vidal wrote a silly introduction about the state of criticism, saying that the kind of criticism he admired was exemplified by Alfred Chester’s review of City of Night. I couldn’t believe it. I wrote him. He didn’t write me back, but in the closest he came to an apology, he told my agent’s wife he probably had been under “Alfred Chester’s evil spell,” and that he admired City very much.

JR: I had been in New Orleans for Mardi Gras. I was unsure of my future, all f––up on pills, drinking, all kinds of stuff. I returned to my mother’s house in El Paso. One day I rented a typewriter and wrote this desperate letter about the nights I had spent in New York, Los Angeles, and New Orleans. I put the letter away. Then, a few days later, I came across it. I changed a couple of things and sent it to New Directions and Evergreen Review. James Laughton [of New Directions] wrote me a very kind letter. He wanted to publish “Mardi Gras,” but the anthology had already gone to press.

JR: Don Allen, a Grove editor, was considering “Mardi Gras.” He wanted to know if it was part of a novel. It wasn’t, but I said it was. It was halfway a lie. “Mardi Gras” was published after I moved back to L.A. Don came out to see me. He was interested in a manuscript that did not exist. I told him I was not yet ready to show it.

JR: I felt it would be a betrayal to expose to judgment the people I had lived among, but if I didn’t, their lives would disappear completely.

JR: That was the core of the book, “The Fabulous Wedding of Miss Destiny.” I re-wrote it several times. Barney Rosset kept rejecting it without explanation. Don suggested I send it to Big Table. They published it, and I began to receive letters from Jason Epstein at Random House and others. Don Allen then offered me a contract and modest advance.

JR: I was living in a dingy hotel on Hope Street and working at temp jobs. I stayed away from the scene. I felt guilty. I didn’t want them to see me. I didn’t want them to think I was a voyeur.

JR: I wrote every day, frantically. The chapters were out of sequence, each a portrait—Miss Destiny, Chuck, the L.A. cowboy. My mother and brother helped me collate it. When the galleys came back, I panicked. It was remorselessly awful. I could not believe I had let it go out. I made little changes. I couldn’t stop. I revised the whole book, retyping, pasting. I called Don. He almost fainted. Grove had wanted to enter it in a contest. But when he saw what I had done, he felt strongly we had to make the changes. They reset the book and the publication date was rescheduled.

JR: Because I can still feel the excitement of that scene, being right on the edge, among all these people dancing on the void. The exhilaration was enormous. You had to live because you were so close to falling over. It was like a drug. On the opposite side, there was darkness. I still think of it that way.

JR: Miss Destiny became notorious. She was sought after by one magazine that put her on the cover in drag. She gave a nasty interview. It was very funny. She would call at 3:00 a.m. when she got a husband. He didn’t believe she was a character in a book. I was delighted.