|

|

From the first week in law school to preparing an appellate brief, lawyers are trained to spot issues: Was there an offer? Or a mere inquiry? Was the whole deal illusory? So it is something of a surprise that the legal profession missed the issue when Tom Girardi, the highly successful trial lawyer, fell from grace and was accused of stealing millions from clients: “widows and orphans,” as the press put it. One lawyer called it “a betrayal” of the entire profession; another prominent trial lawyer, who is now the subject of a bar inquiry himself over disputed client funds, viewed the matter somewhat kinder: “You want to be David fighting Goliath,” he said of the high living Girardi who was married to a reality television star. “You don’t want to be a Goliath.” And yet: not the Chicago federal judge who proved to be Tom Girardi’s undoing, not the belated state bar opinion that disbarred him, not the recent news story that Girardi’s firm’s financial officer was double-dipping–spotted the real issue:  How do you judge immoral conduct in an amoral setting? Every story has a beginning, and Tom’s did, too, as a young boy in Colorado watching Perry Mason–that old tricky trial lawyer–on television and dreaming that someday he would wow judges and juries; and it was fitting that the seed of glory was planted by television–and not in some musty library reading old Clarence Darrow summations–for television shaped the image of the L.A. lawyer–where everyone is rich, goes to Harvard, and has great hair. Reality is always another matter, especially in California, where each year graduates of some funky law school come on the market, hanging out their shingle in a one room office or taking space–sometimes only a desk–in a so-called Fegen Suite, a floor of offices set aside just for lawyers. That arrangement was pioneered in the 1960s by Paul F. Fegen, a USC Law grad, who got overextended on leases, went broke, and–finally–was disbarred. The small practitioner was the route young Tom Girardi took. After his family moved to California, he grew up in Westchester, a blue collar Los Angeles suburb–James M. Cain land–and went through Loyola Law, one of the Jesuit-sponsored academies, found in every big city, that prepare stout Irish lads for a career as insurance lawyers or ready sharp Italian boys-like Tom–to go on their own. “You eat what you kill,” young trial lawyers like to say; and when Tom started his two man partnership–Girardi & Keese–in 1965, he supped on a slender diet of auto cases and slip and falls–the latter a gift from the supermarkets that spawned throughout the vast L.A. metropolitan area. “Mrs. Fernandez, can you step down from the witness stand and demonstrate for the jury how you walk because of your injury?” was a favorite tactic of the late Elmer Low who wrote the book on trying personal injury cases.

Tom Girardi proved as smooth as the smoothest of them, charming juries made up of civil servants and retirees–ordinary folks–to hand over insurance company dollars; and he was different from the billboard warriors who pride themselves on aggressive behavior. Outside the courtroom, he was well-liked and polite, even to other lawyers, including adversaries.

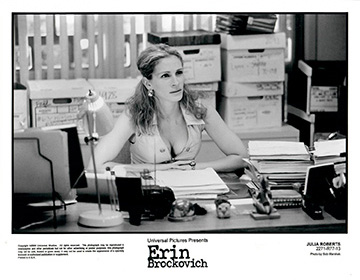

In a profession of superegos, Girardi seemed self-effacing. When he was portrayed on the screen in Erin Brockovitch, a film based on one of his toxic tort cases, Tom joked that the actor who portrayed him was better looking than the one who played the insurance lawyer. Even today, Greg Rizio, head of a plaintiff lawyers association, says: “I always liked Tom, though I sometimes doubted his sincerity.”

Starting in the 1970s, the Girardi-Keese cash register started to ring up big numbers as Tom moved into toxic torts and airline disasters. Lockeed, Merck, Hollywood coughed up millions to make Tom go away–or take a beating at trial.

Tom was never a legal scholar or theorist. His forte was working juries, and he earned his place among the legendary California trial lawyers: Jake Erlich of San Francisco, Melvin Belli, the self-styled “King of Torts,” who pioneered product liability law, and Jerry Giesler, of “Get me Giesler” fame, who got Errol Flynn off in his sensational 1943 statutory rape trial.

As Tom’s fame grew, other lawyers referred him cases. These were usually small shops or sole practitioners who had lucked into a big case, often a class action where they had locked up the class rep, but needed someone with Tom’s experience–and deep pockets–to carry the load. In exchange for turning over the case, or serving as titular co-counsel, they received a “referral fee.” This was usually 20% of the haul, which in a class action could run into millions (in theory anyway).

Erin Brockovich, which settled for over $300 million, then a record, was such a case, but there were others, including the 1994 Northridge earthquake and airline crashes.

The Los Angeles legal community is a rumor mill: sitting in court waiting for the judge to take the bench or grabbing coffee at the Central District Court cafeteria, attorneys gossip about judges to avoid or who brought in a “nice verdict” (or “got defensed”).

So over the years, there were stories about Tom Girardi: How as president of the Italian-American Lawyers of Los Angeles, he picked up the tab for monthly meetings that were held, not at their regular banquet hall in Chinatown, but at Spago’s or the Jonathan Club, once the mark of old money. Such anecdotes burnished the legend of Tom, the easy going sport, the (only) lawyer everybody liked, but there was at least one story that showed he knew how to play the system.

Supposedly, his firm had missed a statute, screwed up a case, and instead of informing the client, as he was ethically obligated to do, Tom called them in and handed over a check for a hundred thousand dollars–congratulating them on beating the insurance company. Then, beginning in the 1990s–when the big money flowed in–tales began to circulate that Tom Girardi was reneging on referral fees. As Los Angeles magazine later reported, it became a “kind of running joke.” In his charming way, Tom would call the other lawyer and say: “Hey buddy, this case...didn’t do very well, we can’t pay a referral fee,” and then promise to refer a case in exchange.

In California, such a scenario is not uncommon. Tom Girardi was hardly alone in welching on referral agreements. A loophole is built into the state rules of professional responsibility which insist that any fee splitting arrangement must be in writing and signed by the client. A handshake is not enough to seal the deal, even if the client verbally assents, so has held one appellate court. Margolin v Sherman, 85 Cal.App. 4th 89 (2000) The California Supreme Court approved this holding, explaining its purpose is “to promote respect and confidence in the legal profession.”

Tom was hit with a few lawsuits by lawyers who were bold enough to challenge him, but these were quickly settled. As a heavy donor to the Democratic Party, Girardi had influence in the appointment of judges, some of whom owed their jobs to him, and an aura of immunity grew up around him.

It was Felix Cohen, the son of a philosopher, and namesake of a cerebral U.S. Supreme Court Justice, who coined the term “robe magic.” By that he meant that once a person took the bench, and was addressed, “Your Honor,” he (or now she) became, in their own mind, “the personification of justice ” (and so would rule impartially). Another student of power, the young Don in-waiting in The Godfather, proved more skeptical of human nature. “Now who’s being naive?” he asked, when told that presidents don’t have people killed.

So whether Tom Girardi needed to corrupt anyone is an open question. Every practicing lawyer in Los Angeles has heard one or two stories that didn’t involve Girardi: of the judge who comes out of his chambers red-faced after a brief trial break and dismisses the case in a fit of pique (Full disclosure: my former firm tried the case and reversed it on appeal.); or the jurist who rushes past the morning calendar so he can make the races at Hollywood Park; or the judge who appears at the family dinner table in his black robes, maybe in an eerie tribute to Mr. Cohen.

Trial judges keep their appellate brethren busy correcting their misbehavior. See, e.g., People v Nieves, 11 Cal.5th 404 (2021) (judge’s sarcasm “undermines fairness”) Yet, at the appellate level, traces of bias in a court’s ruling are not unknown. Attorneys sometimes call it: “What the judge had for breakfast”; and there was once a school of thinkers, among them Professor Karl Llewellyn, author of the treatise Deciding Appeals, who championed this view, known as Legal Realism. That school is long out of fashion but survives on a daily level to the working lawyer.

For example, there are some appellate judges who will go out of their way to shield public entities from civil liability–a holdover not only from the days of sovereign immunity-“The King can do no wrong”–but as a way of protecting sagging pension funds and tax payer dollars.

In one recent California appellate decision, Victor Valley Union High School District v. Superior Court, a jurist with a strong civil service background, found that a school district should not be sanctioned for destroying evidence in a child molestation case. The reasoning turned on statutory interpretation of a so-called “safe harbor” provision, in which the court found that since there was only “the possibility” of a lawsuit by the victim’s parents, the District was not obligated to preserve evidence of the alleged molestation.

Among the trial bar, public entities are revered as “deep pockets,” and suits are filed against them in the thousands, so it was a safe bet–”foreseeable” in legal jargon - that a lawsuit would be forthcoming. What the judge had for breakfast is another matter.

In any event, Thomas Vincent Girardi is in the criminal dock, charged with stealing $18 million from clients in what the Los Angeles Times calls “a long running Ponzi scheme.” Even the IRS has gotten into the act trying to recover lost tax revenue. A member of the Criminal Investigation unit assured the press that “along with..our law enforcement partners,” the IRS “will continue to seek to keep the legal profession honest.”

An eager U.S. Attorney named Estrada has vowed to put Tom away, but others remain dubious. The accused is 82 and last summer was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s. This has raised due process concerns that if Girardi cannot assist his lawyers in preparing their case, he may not be found competent to stand trial.

Some federal judges have gotten around this constitutional obstacle. Mia Yamamoto, a criminal defense lawyer, told the L.A. Daily Journal, a legal newspaper that, in the past, federal judges have allowed defendants deemed incompetent to be “drugged up” and brought to court.

“They’re really only half there,” Ms. Yamamoto was quoted as saying. “They’re not completely here and maybe none of us are. But it’s enough for the judicial process to proceed.”

Will Tom walk or won’t he? At this point, no one knows. Maybe the verdict rests with that old issue spotter, comedian Lenny Bruce. It was the late Mr. Bruce, no stranger to the courtroom, who said: “In the Hall of Justice, the only justice is in the hall.”

Dino Garonshon for AL. Dino is the pen name of an attorney-writer who has written about Israel and other contemporary issues. This essay is dedicated to the memory of Allan Axelrod, late Visiting Professor of Law at USC Law Center. |